Surfacing Innovation in Bureaucracy

Diving deep to support innovation in large organizations

By Nick Scott

Innovation can seem impossible in a bureaucracy. Despite all the talk of change and transformation, progress can feel slow and superficial. In a world where the pace of change outstrips our bureaucratic processes, true innovation within large organizations isn't just an option; it's a necessity for survival and effectiveness. In the context of government, reputation and trust depend on it. The big question is: How can public sector organizations balance the need for innovation with the imperative of maintaining stability and public trust?

All transformation results in change, but not all change is transformative. Transformative change goes beyond surface-level adjustments. It involves completely new ways of thinking about and seeing the world. It’s about introducing entirely new practices and approaches to how solving problems and creating value. The kind of change needed today is transformational, and innovation labs - among other types of spaces to prototype novel ways of working - are the most promising ways to break free from the dependent path of bureaucratic organizations.

Creating space to prototype culture change is the most promising way of breaking free from the dependent path of bureaucratic organizations.

Government leaders and executives often emphasize the importance of adopting whole-of-government strategies that ensure smooth and cohesive service delivery to the public. We advocate for embracing digital technologies, adopting ethical artificial intelligence, and creating an “omnichannel” experience for citizens.

These are lofty and worthwhile goals.

However, our bureaucracies were not originally designed to achieve these objectives. Additionally, innovation if often treated as a nice-to-have or merely virtue signaling. As Jenny Lewis puts it, referring to the rise of innovation labs in government:

“A more critical reading of this situation would extend this to the possibility that design approaches and labs, when they are the methods and organizations hosting the design of policy, are more important for signalling a government’s innovation credentials than for doing anything novel.”

Innovation is imperative despite the possibility that governments engage in this kind of signaling. Regardless of your sector, I believe innovation is worth saving from the buzzword abyss.

We've seen how imposing large-scale change and superficial innovation initiatives can result in fatigue and disillusionment. It is possible to avoid these performative strategies and actually achieve meaningful results within government. However, achieving such results requires us to be ready for discomfort, to unlearn old ways, and to consider changing the established formal and informal structures of our organizations. Innovation labs can offer a secure space for us to embrace this process and find a way to make our organizations more innovative.

An innovation lab with a Theory U compass can explore the depths of culture needed for transformation in ways that the SS Bureaucracy cannot.

The OECD Observatory for Public Sector Innovation defines innovation as the realization of:

New products, services and processes

New policies and systems

New ways of thinking and of understanding the world

New ways of acting, organizing and relating to the world.

This definition is great because it encompasses various types of innovation that can lead to improvements in policies, programs, products, and services. Innovation in the latter two categories can result in transformative change. Now, let's explore this idea further by suggesting that these transformative innovations are essential for creating viable innovations in the former.

When seeking out new products, services, processes and policies, ask yourself this question from Mel Conway (Conway’s Law): “Is there a better design not available to us because of our organization?”. Fragmented organizations deliver fragmented experiences.

Further reading: How internal information silos lead to a fragmented user experience.

SS Bureaucracy: It ships, but it doesn’t dive deep

An organization maintains the systems and fundamental structures that lead to its outcomes and impacts. Calls for "innovation" suggest that the current results and offerings are not meeting expectations and need to be transformed. However, any effort to alter these outcomes and impacts without innovating the foundational system will likely fail. Culture has a powerful influence beyond strategic planning, and true change can only be achieved through a culture shift.

Tamami Komatsu (et al.) discuss the importance and challenges of going deep into an organization to co-design services with citizens (emphasis added):

“This [user-centred design] approach encourages public sector organizations to take a deep look into the lives of citizens and provide value as it is needed rather than seeking to do more of what they already do. In other words, the challenge is to create the value proposition based on the citizen’s real needs — often in relation to other services coming from other agencies — and then to align internal processes accordingly. This provides an interesting perspective for innovation in the public sector, given the fragmented nature of its supply — i.e. the numerous agencies that are involved in satisfying public needs — by encouraging the sector to look at how citizens use public services in response to life events.”

Public service innovation demands that public sector organizations not only interact with users in fresh ways but also collaborate amongst themselves. This collaboration is necessary to move beyond simply repeating existing practices and to reconfigure internal structures in line with citizens' needs.

These types of interventions, however, must go beyond a cosmetic use of design that seeks to merely make services look better. A quick example of such initiatives can be seen in digitalization initiatives that merely change the visual identity of the website without changing the offer or re-organizing content and flow to improve the experience of citizens or make their journeys easier (Komatsu et al.)

Innovation requires more than superficial changes. As Komatsu (et al.) put it: “[cosmetic efforts] fail to re-design services based on a re-framing of the problem but rather employ design tools to embellish or re-market existing services.”. Reframing the current situation and problems to support “the realization of new ways of thinking and understanding the world.” is a necessity to innovation according to the OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation. Human-centered design is an approach that can facilitate this reframing by engaging citizens, however its application is far from consistent in the public sector.

Episodic use of design — by failing to engage in strategic design — hinders transformative change. This is in line with how innovation in the public sector has been described in literature: as being episodic (Sørensen and Torfing 2011, p. 847), “driven by accidental events that do not leave public organizations with a lasting capacity to innovate” (Eggers & Singh, 2009). (Komatsu et al.)

Focusing innovation efforts on new policies, processes and services without addressing the underlying ways of acting, organizing, thinking, understanding and relating to the world is akin to “rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic” … or on SS Bureaucracy, for that matter.

This brings me to icebergs.

Innovation beyond the visible tip of the iceberg

Think of the OECD OPSI definition of innovation as an iceberg. The first two types represent what's visible above the water's surface, while the latter two remain hidden beneath. To achieve true transformation, innovation needs to reach these concealed depths. A dive into the culture of an organization is essential.

This brings us to iceberg number two: corporate culture.

Culture is deeper than strategic plans and vision statements

… but that’s the level typically visible to SS Bureaucracy. Beneath the surface lies an array of invisible and intangible cultural components and informal social structures that influence the observable outcomes.

To achieve transformative change, we must be willing to explore these profound depths. Yet, this endeavor can be unsettling and unfamiliar. Moreover, SS Bureaucracy is not equipped to delve into these unseen layers. This is understandable, as bureaucracy is preoccupied with stabilizing and managing the observable effects that float at the surface.

A rather famous framing of corporate culture as an iceberg. Lynch, N. (2017). The Cultural Iceberg Explained. Available: https://www.lynchlf.com/blog/the-cultural-iceberg-explained/

This brings us to the last iceberg model that will help chart a course for organizational transformation.

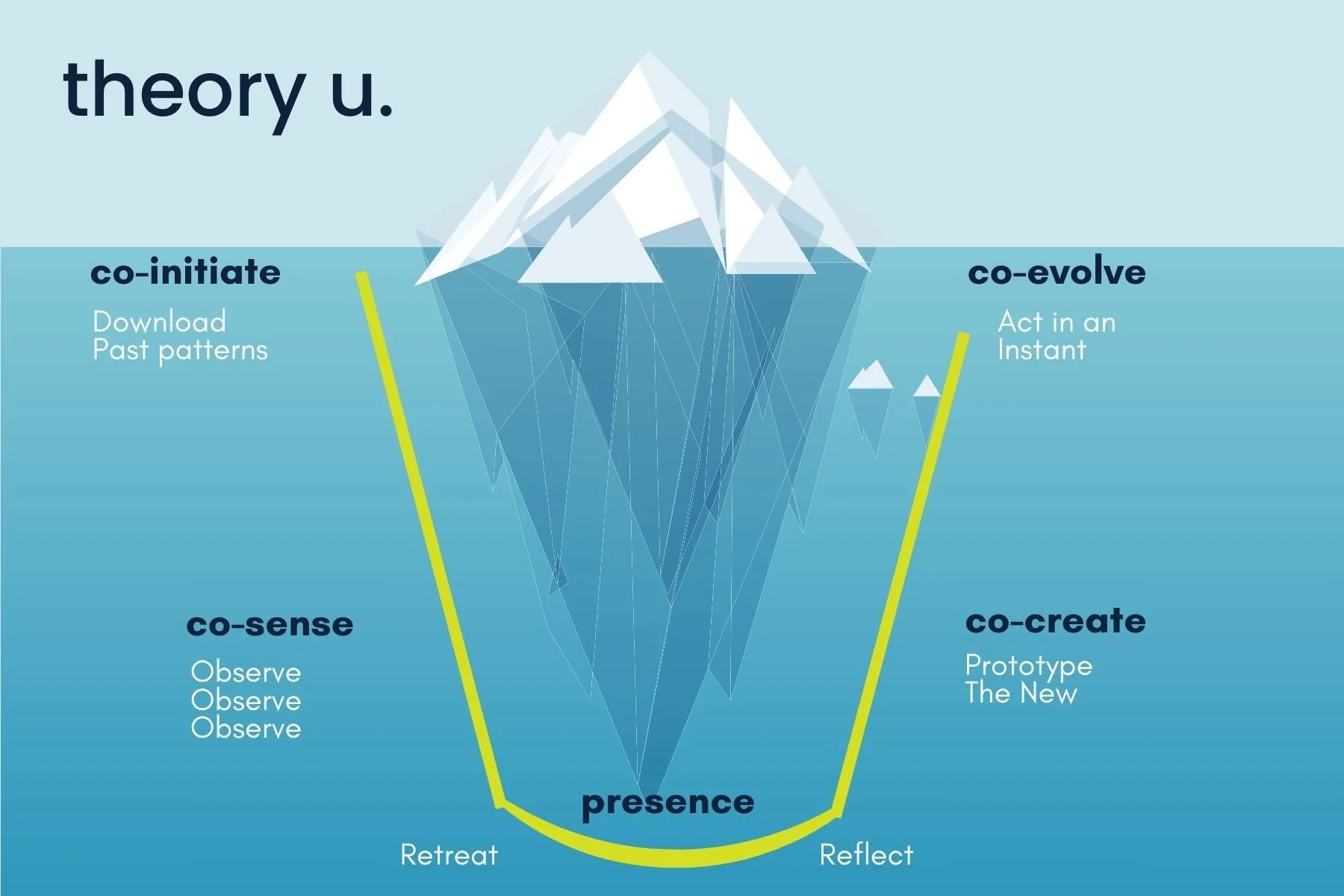

Theory U

Theory U stands as a method for managing change that facilitates collaboration and innovation. It presents an approach that guides individuals from a narrow individual perspective to a broader collective understanding of the world. This method enhances awareness of systems by fostering empathy and encouraging introspection among group members.

Utilizing Theory U can empower any transformation initiative to chart its actions and navigate its path to delve beneath the surface barriers that impede change efforts. Innovation labs (studios, accelerators, incubators, etc.) equipped with this framework can serve as potent catalysts for organizational change.

Theory U Process and The Iceberg Model. I like this explanation: https://donellameadows.org/systems-thinking-resources/

SS Labo: The Role of Labs

Governments need to approach change a little more cautiously than the private sector. This is because stability is a priority of the government, and the sheer scale of the potential risks of public harm and damaged trust surpasses that of any particular business.

“… public sector innovation is stuck between the need for change and the need for stability. Public bureaucracies must somehow succeed at the balancing act of unleashing innovations while also maintaining socio-political stability.” (Lewis)

Conversely, failing to effectively change, and adapt to the demands of our environment, risks public harm and damaged trust, too. Risk is inherent in the status quo.

So we need to figure this out.

Innovation labs can de-risk organizational change. They provide space and a facilitated practice for groups to develop a shared understanding of a problem and experiment with potential solutions. Innovation labs coupled with the functions of a parallel learning structure are a promising way of de-risking innovation, fostering organizational learning and advancing transformation.

An innovation lab with a Theory U compass can explore the depths of culture needed for transformation in ways that the SS Bureaucracy cannot.

This means that the work of a lab cannot stay in the lab, or the fruit it bears risks withering on the vine.

“The answer, they claim, is for states to support “innovation bureaucracies” — constellations of public organizations that are capable of delivering agile stability. If governments create new organizations (like labs) which are led by charismatic outsiders, but these people and their networks do not become part of the routine of government, innovation in the public sector will not be sustained.” (Lewis)

Labs operate and explore along the path of The Emergent System by building networks of innovators, making space for prototyping culture change, and growing influence by showing results. The Moment’s explanation of The Berkana Two-Loops Theory and Systems Change is one of the best I’ve read.

Conclusion

Creating a place where you can freely experiment with new ways of thinking, understanding the world, organizing and acting, is vital for enabling innovation. It’s like playing a sport, performing on stage, or cooking. Reading about it, sending emails, and having meetings won't magically improve you as a player, performer or cook. The same principle applies to striving for digital transformation, enhancing your organization's expertise in a certain field, or helping your organization adapt to a changing environment.

Practice shapes us. Allocating time and space for practice is a surefire way to bring about organizational change. The processes and outcomes generated in a lab allow you to showcase the value and potential of your ideas, not just talk about them. Your colleagues will believe it when they see it; they will be changed when they experience it. This is how a movement is built, one step at a time, spreading innovation with unstoppable momentum. The alternative path will become irresistible.

References / Sources

Elisabete Ferrarezi, Isabella Brandalise & Joselene Lemos (2021) Evaluating experimentation in the public sector: learning from a Brazilian innovation lab, Policy Design and Practice, 4:2, 292–308.

Hawk TF, Zand DE. Parallel Organization: Policy Formulation, Learning, and Interdivision Integration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2014;50(3):307–336. doi:10.1177/0021886313509276

Lewis, Jenny M. (2021). “The limits of policy labs: characteristics, opportunities and constraints.” Policy Design and Practice, 4:2, 242–251.

McGann et al. (2021). “Innovation labs and co-production in public problem solving.” Public Management Review. Vol. 23, №2, 297–316.

Stoll, Aline and Kevin C. Andermatt. (2021) “Tab the Lab: A Typology of Public Sector Innovation Labs.” Conference Paper IRSPM.

Sydow, Georg & Schreyögg, Georg & Koch, Jochen. (2008). Organizational Path Dependence: Opening the Black Box. Helfat Huff & Huff. Gilbert. 10.5465/AMR.2009.44885978.

Tamami Komatsu, Mariana Salgado, Alessandro Deserti & Francesca Rizzo (2021) Policy labs challenges in the public sector: the value of design for more responsive organizations. Policy Design and Practice, 4:2, 271–291.

Whicher, Anna (2021). Evolution of policy labs and use of design for policy in UK government, Policy Design and Practice, 4:2, 252–270.